UK Workers Gain Bigger Share of Economic Output

Because of ongoing labour shortages and substantial pay increases, British workers are getting more of the country’s economic output than since the early 2010s. As companies struggle to preserve profit margins and face unprecedented pressure to raise wages, this trend represents a significant economic power shift.

According to a recent examination of official figures, the labour share of the economy, or the percentage of GDP allotted to wages, has increased to slightly less than 50%. Compared with the 48% recorded in 2017, this represents a notable rebound. Employers have had trouble passing on the cost of rising salaries to customers, which has resulted in lower profit margins.

A Balancing Act Between Wages and Inflation

As policymakers attempt to control inflationary pressures, the Bank of England has noted that companies are absorbing wage increases rather than passing them on to consumers. This trend provides some comfort. A lower ability to raise prices suggests that inflation, which has been the central bank’s major worry in recent months, may be waning.

Economists believe wage dynamics and this redistribution are tightly related. Paul Dales, chief UK economist at Capital Economics, highlights that wage growth is currently outpacing pre-pandemic levels, even as it begins to moderate. “Labour share is being driven by wage growth really. Before the pandemic, wage growth was unusually low by historical standards. But since the pandemic, wage growth has gone up quite a lot,” he explained.

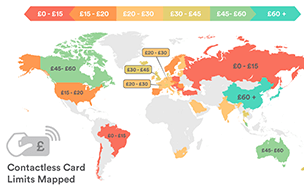

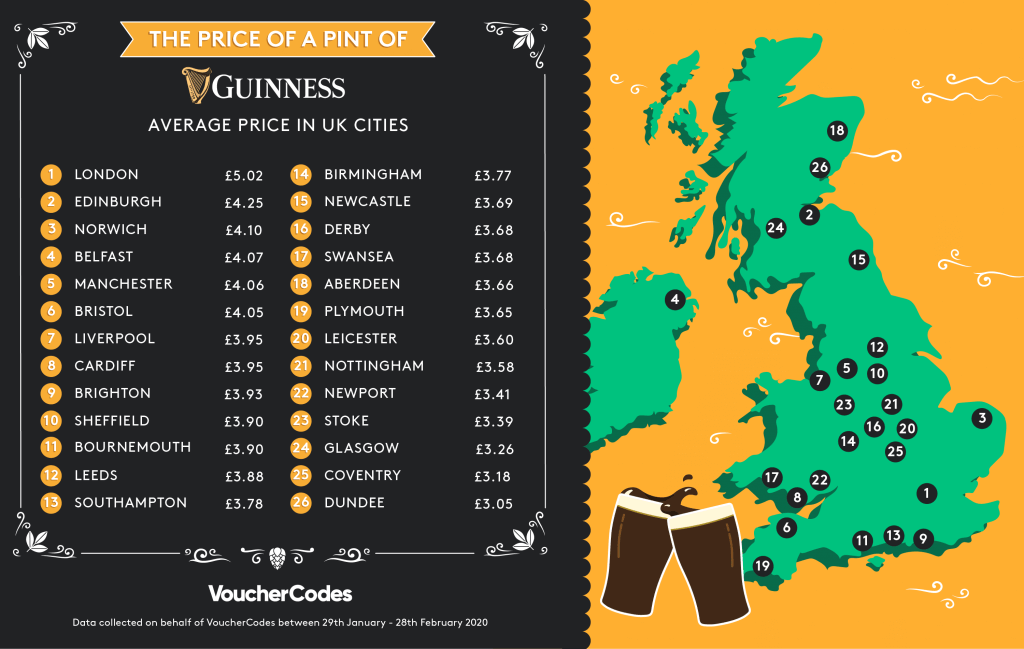

Regular wage growth reached an annual rate of around 8% a year ago and remains close to 5%, signalling a sustained improvement in workers’ pay. In real terms, wages are once again rising, further strengthening employees’ position in the labour market. With wage growth improving, those with higher wages have more disposable income to save.

What’s Driving the Shift?

Several factors have contributed to this rebalancing of economic power. Increased health-related inactivity has led to a workforce shortage in sectors including construction and hospitality, increasing competition for skilled workers and raising salaries. The government’s decision to increase the minimum wage and introduce a £26 billion increase in the national insurance payroll levy has further bolstered workers’ earnings.

However, these actions have made things more difficult for companies. Many businesses lack the pricing power necessary to raise prices to offset increased labour expenses, while the UK economy shows signs of weakness. As a result, the economy’s profit share has decreased and is now at its lowest point since 2007, according to the Bank of England.

Small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs) are especially hard hit. In its latest Monetary Policy Report, the Bank of England raised worries about smaller businesses’ declining cash reserves, especially in customer-facing industries like retail and hospitality. These companies are facing the dual problems of increased expenses and decreased profitability as they are unable to raise prices owing to the lack of demand.

The End of “Greedflation”?

The results also call into question claims of “greedflation,” a phrase used to characterise companies accused of taking advantage of inflationary circumstances to increase prices without justification. Rather, employees and businesses seem to be having difficulty recovering losses brought on by the last few years’ economic shocks.

Cost constraints on consumers and companies have been substantial, ranging from supply chain disruptions brought on by the pandemic to the dramatic increase in food and energy costs after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Workers have benefited somewhat from wage rises, which have helped counteract the effects of inflation, even if businesses have had their profits pinched.

Is the Trend Here to Stay?

It is unclear whether this increase in the labour share is a short-term adjustment or a long-term change. According to economists like Benjamin Caswell of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, more time is required to assess the long-term effects. “It’s something to watch, particularly in the coming years, as we see robust wage growth and announced budgetary measures,” he added.